There was a bed outside for Willow. It was in the same place that Zuri used to like. Willow never used it. It was there for weeks: solitary, unused.

1. She didn’t like it because it smelt like Zuri.

2. She didn’t like the type of bed; it’s height, shape, size, fabric.

3. She preferred to lie on the decking.

4. She preferred to lie in the sun.

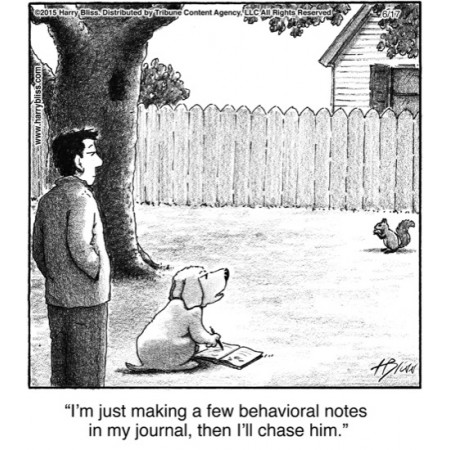

There’s no way I can get inside her head to know what’s going on, but I can watch her behaviour and notice things. She didn’t use the bed. She lay in the sun. She lay on the decking. She seemed to like particular spots on the decking. She liked to sit on the outdoor chair. So I moved the bed to one of the spots on the decking near the outside chair. That’s all it took. I was actually surprised. This was the first attempt at problem solving how I could get her to use it. I had been prepared to keep problem solving.

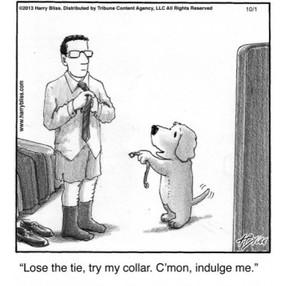

What I’d like to express with this example is that dogs have preferences and if we acknowledge these it can make every day life and training easier. We often want to train dogs to do things that make our life easier but neglect to take into account their preferences. Teaching a dog to go to a bed is a very handy task. It can give the dog somewhere to go when visitors are around or when dinner is on the table instead of jumping up or begging for food. I often ask people, “Where does your dog like to rest most often?” If the dog has already chosen a spot they gravitate to, I like to start the training to stay on the bed in that area. Of course I can pick a new area and teach the dog to stay there, no problem, but it’s a little easier if the dog has already chosen the place. Plus I feel it’s nice to recognize the dog’s preferences and accommodate this when helping them learn how to fit into our world.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed